Андрей Иванов

Опыт Мондрагонских кооперативов: уроки для России

Ист.: http://fecoopa.narod.ru/mondragon.html, 17.9.2004

См. на англ.: http://www.mondragon.mcc.es/ing/index.asp

http://cog.kent.edu/lib/MathewsMondragon_(COG)_rtf.htm

http://www.ac.wwu.edu/~khoover/Mondragon.html

Arizmendiarrieta

Сборник докладов на английском, в основном вообще о католическом социальном

учении и бизнесе: www.stjohns.edu/pls/portal30/ sjudev.retrieve_edu_img_data?img_id=4258

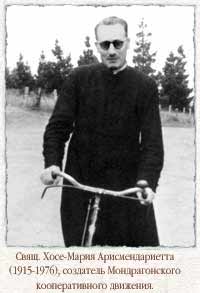

Отец Хосе еще молодым в 1941 году был послан в Страну Басков, вел катехизис,

преподавал социальное учение студентам, в 1959 пятеро из них объединились в кооператив

(делали керосинки).

Мондрагонская

кооперативная корпорация представляет собой, пожалуй, наиболее интересный пример

"экономики участия" - то есть такой экономической системы, которая основана

на участии работников в собственности, управлении и доходах. Мондрагонская

кооперативная корпорация представляет собой, пожалуй, наиболее интересный пример

"экономики участия" - то есть такой экономической системы, которая основана

на участии работников в собственности, управлении и доходах.

Мондрагонская кооперативная корпорация получила свое название по имени небольшого

городка Мондрагон, расположенного в горах на севере Испании,

в стране Басков. Свою историю она ведет с 1956 года, когда в этом городке был

основан первый производственный кооператив, принадлежащий рабочим. Пример Мондрагонских

кооперативов интересен во многих отношениях. Первое, что сразу бросается в глаза

при знакомстве с этим опытом, - масштаб. Если большинство коллективных предприятий

на Западе представляет собой мелкие фирмы, реже- средние, и совсем редко - крупные,

то Мондрагонская группа кооперативов выделяется даже на фоне самых крупных акционерных

предприятий, находящихся в собственности их работников. Это огромное производственное

объединение, охватывающее около 180 (из них более 90 - промышленные) мелких, средних

и крупных кооперативных предприятий различных отраслей. В 1995 году в этих кооперативах

было занято 26 тысяч человек, а совокупный объем продаж Мондрагонской кооперативной

корпорации (МСС - Mondragon Coooperative Corporation) превысил 4 млрд. долларов.

Вторая черта Мондрагонских кооперативов, отличающая их от отдельных кооперативных

или акционерных предприятий, принадлежащих работникам, - наличие так называемых

опорных структур. МСС - не просто конгломерат кооперативных предприятий. Помимо

тесной технологической зависимости, объединение Мондрагонских кооперативов обязано

своей прочностью также целому ряду пронизывающих всю эту кооперативную корпорацию

структур, причем не только экономического порядка. Главная из этих опорных структур

- кооперативный банк (Caja Laboral - Трудовой Банк). Все Мондрагонские кооперативы

связаны со своим банком договором об ассоциации - это значит, что все свои средства

они держат в этом банке, все расчеты проводят через него и обязаны придерживаться

общих экономических принципов, установленных договором (в частности, руководствоваться

типовым Уставом). Взамен кооперативы получают надежный источник кредитов, предоставляемых

по льготным ставкам (кооперативы платят за кредит более низкий процент, чем все

остальные клиенты банка).

В рамках Трудового Банка (первоначально - в качестве его предпринимательского

отдела, а затем - выделившись в самостоятельную структуру) получила развитие система

подготовки, планирования и финансирования создания новых кооперативов. Участники

инициативной группы, предполагающие создание нового кооператива, получают ставку

в Банке и затем, при помощи его специалистов и за его счет, проводятся беспрецедентные

по длительности (два - два с половиной года) и по сложности исследования рынка

для нового кооператива. По завершении этих исследований составляется детальный

бизнес-план, который, после экспертизы Банка, дает основания для получения в первый

год работы кооператива беспроцентного, а в последующие два года - льготного кредита

на его развитие. Если новый кооператив выделяется из уже существующего, он получает

поддержку (кадровую, финансовую и т.д.) и от него. Об эффективности работы такого

"кооперативного инкубатора" можно судить по тому, что из многих десятков

созданных таким образом кооперативов обанкротился пока лишь один.

Другая опорная структура - два кооператива, осуществляющих научно-исследовательские

и опытно-конструкторские работы. Значительная часть современных изделий, выпускаемых

МСС (например, промышленные роботы), разработана этими кооперативами. Они же разрабатывают

и схемы технологических процессов на предприятиях корпорации. Об уровне этих разработок

может свидетельствовать хотя бы факт участия исследовательских кооператив МСС

в разработках НАСА и в европейской космической программе.

Третья опорная структура - кооперативы социального обслуживания. Поскольку

по испанскому законодательству члены кооперативов не относятся к наемным работникам

и на них не распространяются соответствующие правила социального страхования,

то Мондрагонские кооперативы еще в начале 60-х годов создали собственную систему

социального страхования. При более низких взносах на одного работника, чем в государственной

системе, она обеспечивает медицинское обслуживание гораздо более высокого качества

(система медицинского обслуживания в МСС признана в Стране Басков образцовой)

и более высокий уровень пособий по безработице.

Наконец, четвертая (последняя по счету, но отнюдь не по значению) опорная структура

- система образовательных кооперативов. Она включает сеть школ, профессионально-техническое

училище, политехнический институт, институт промышленного дизайна, курсы подготовки

менеджеров, курсы повышения квалификации специалистов и целый ряд других. Некоторые

исследователи даже считают точкой отсчета истории Мондрагонских кооперативов не

1956 год, когда был основан первый производственный кооператив, а 1943, когда

начало действовать кооперативное профессионально-техническое училище.

Кооперативы, входящие в МСС, построены на одинаковых принципах, соответствующих

международно признанным кооперативным принципам (один человек - один голос; каждый

новый член кооператива может вступить в него на тех же основаниях, что и ранее

вступившие и т.п.). Члены кооператива на общем собрании (не реже раза в год; участие

в собрании - не только право, но и обязанность члена кооператива) избирают Правление,

которое назначает управляющих, и утверждают распределение прибыли по итогам года.

Членами правления являются только члены кооператива. На время выполнения функций

членов правления за ними сохраняется прежняя зарплата. Управляющие в состав правления

не входят. Кроме правления, члены кооператива избирают Социальный совет, который

выполняет примерно те же функции, которые обычно исполняют профсоюзы. Впрочем,

в кооперативах могут действовать и профсоюзные организации.

Вступительный взнос в кооперативы примерно равен годовой зарплате неквалифицированного

рабочего и составляет около 10 000 долларов. Для его уплаты предоставляется рассрочка

от двух до четырех лет (для сравнения - стоимость создания одного рабочего места

в Мондрагонских кооперативах превышает 100 000 долларов). Вступительный взнос

члена кооператива зачисляется на его индивидуальный счет капитала.

Заработная плата в кооперативах построена на следующих трех принципах - 1)

внешняя солидарность, означающая соответствие уровня оплаты в кооперативах тому

уровню, который определен тарифными соглашениями в частном секторе; 2) внутрення

солидарность, означающая сведение к минимуму различий между членами кооператива,

основанных на разнице в доходах (высшая зарплата не может превышать низшую ставку

неквалифицированного рабочего более, чем в 4,5 раза); 3) открытость условий оплаты,

что означает свободу получения любым членом кооператива информации о любом окладе.

Кроме заработной платы, по итогам года часть прибыли распределяется пропорционально

индивидуальным счетам капитала, плюс к тому на средства на этих счетах начисляется

обычный банковский процент. Только этот процент работник может получить наличными,

а основную сумму выплачивают лишь при уходе из кооператива по старости или по

болезни. Свой счет можно передать и по наследству, но при условии, что наследник

будет работать в кооперативе.

За 40 лет своего существования Мондрагонские кооперативы прошли большой путь.

Если первые кооперативы производил продукцию такого рода, как, например, кухонные

плиты или простейшие отливки, то сейчас более 90 промышленных кооперативов производят

гораздо более широкий круг весьма совершенных промышленных изделий. Среди них

большой набор потребительских товаров - автоматические стиральные и посудомоечные

мащины, микроволновые печи, холодильники, мебель; оборудование и мебель для торговых

предприятий, в том числе различные водонагревательные приборы; большой спектр

приборов и оборудования для технологического контроля (в том числе используемые

в сложной бытовой технике, производимой кооперативыми); комплектующие изделия

для компьютеров, аудио- и видеотехники; междугородные автобусы и комплектующие

изделия для автомобилестроения; лифты и подъемники; множество видов станков и

инструмента - абразивный инструмент, прокатное оборудование для сложных профилей

проката, кузнечно-прессовые машины и прессы; промышленные роботы и гибкие производственные

системы.

В МСС входят также строительные кооперативы, обеспечивающие жилищное и промышленное

строительство, возведение мостов и крупных оффисных зданий. Есть и несколько сельскохозяйственных

кооперативов различной специализации (молочные, винодельческий, свиноводческий

и др.), занимающихся также переработкой сельскохозяйственной продукции. Наконец,

в состав МСС входит потребительский кооператив Eroski, имеющий огромную сеть магазинов,

супермаркетов и гипермаркетов не только по всей Стране Басков, но и на значительной

части остальной Испании.

Кооперативы Мондрагонской группы обладают значительной устойчивостью - за все

40 лет их существования обанкротилось всего три кооператива (из них два не были

созданы самой группой, а приняты "со стороны"). Этот результат можно

сравнить с нормой, уже ставшей хрестоматийной - в США за первые пять лет существования

выживает лишь 20% вновь созданных мелких фирм.

Помимо "выживаемости", можно обратить внимание и на устойчивый рост

объемов продаж, и на постоянный рост занятости. В чем же секрет такой длительной

успешной работы?

Обычные предприятия, принадлежащие работникам, находятся в очень большой зависимости

от общих условий капиталистического рынка - колебаний спроса на их продукцию на

товарном рынке, изменения условий на рынке капиталов (в частности, уровня процента

за кредит), конкурентной борьбы и технологических нововведений... Не свободны

от этой зависимости и кооперативы МСС, но для них она в значительной степени смягчается

как масштабами кооперативной корпорации, так и наличием опорных структур. Эти

структуры отчасти превращают внешние для изолированных предприятий условия рынка

во внутренние факторы развития.

Мондрагонские кооперативы, разумеется, сталкиваются с колебаниями конъюнктуры

рынка, как и обычные капиталистические фирмы. Однако у них существуют значительные

возможности компенсировать возникающую структурную безработицу - в то время как

одни кооперативы вынуждены свертывать производство и высвобождать работников,

другие, напротив, расширяют дело и привлекают дополнительную рабочую силу. Такому

переливу работников способствует разветвленная система подготовки, повышения квалификации

и переподготовки кадров. За все время существования Мондрагонских кооперативов

было лишь три года, когда происходило сокращение суммарной занятости. Все остальное

время она росла. Общая занятость росла даже в конце 70-х годов, когда Испания

переживала затяжной экономический кризис, а уровень безработицы в Стране Басков

временами приближался к 30%. Наличие собственной системы подготовки специалистов

и управляющих из членов кооперативов позволяет, кроме того, значительно снижать

издержки на найм высшего управленческого персонала. И хотя заработки управляющих

в МСС значительно ниже, чем на сравнимых капиталистических фирмах, кадры менеджеров

и специалистов не уплывают "на сторону", а остаются в кооперативах,

обеспечивая высокий уровень стратегического планирования и организации производства.

Даже в самые тяжелые кризисные годы МСС наращивала производственные инвестиции

(подчас даже за счет замораживания, а то и сокращения заработной платы, проводимого

по решению общего собрания). Такое поведение начисто опровергает расхожее мнение,

что в коллективных предприятиях работники предпочитают все средства направлять

на наращивание заработной платы в ущерб капиталовложениям. Возможность поддерживать

высокий уровень инвестиций определяется тем, что индивидуальные счета капитала

работников, сконцентрированные в Трудовом Банке, составляют значительную часть

его активов и фактически являются гарантированным кредитным ресурсом. Активы Трудового

Банка пополняются и за счет других источников, значительно превысив к 1995 году

3 млрд. долларов. Кроме того, договором об ассоциации предусматривается, что заемный

капитал может составлять примерно половину используемого кооперативами капитала,

остальное же они должны инвестировать сами. С этой целью из прибыли кооперативов

делаются ежегодные отчисления в резервный фонд, колеблющиеся от 20 до 50% чистой

прибыли. Таким образом, Мондрагонские кооперативы не зависят от "внешнего"

рынка капиталов.

Значительно слабее и зависимость МСС от рынка инноваций. Хотя, разумеется,

исследовательские структуры МСС не могут взять на себя все задачи по обеспечению

технологического прогресса, все же зависимость корпорации от рынка новых технологий

значительно смягчается. Более того, МСС сама выходит на рынок со своими информационными

и технологическими продуктами, инжиниринговыми и консалтинговыми услугами.

И все же объяснить феномен Мондрагонских кооперативов только этими факторами

нельзя. Ведь до сих пор МСС остается единственным в мире примером такой крупной

системы, основанной на экономике участия. Следует подчеркнуть, что условия формирования

МСС были во многом уникальными. В период становления Мондрагонских кооперативов

сошлись в одной точке множество неповторимых условий.

Социальная политика франкистского режима была в общем более мягкой, нежели

политика его германского или итальянского аналогов, и, наряду с жесткой антипрофсоюзной

позицией и мелочным административным контролем над предпринимательской деятельностью,

оставляла некоторое место и давала правовую основу для кооперативного движения.

Основатели первых кооперативов обладали довольно необычными для Страны Басков

того времени качествами - происходя из рабочих семей, они получили инженерное

образование. Баски, как национальное меньшинство, обладают высокоразвитым чувством

национальной солидарности, и любое начинание, которое может продемонстрировать

их способность к успешному решению любых проблем - в данном случае экономических

- встречает их поддержку. Этот же фактор обеспечивает высокую внутреннюю солидарность

в Мондрагонских кооперативах, что, помимо всего прочего, объясняется еще и тем,

что МСС успешно решает одну из очень болезненных и застарелых для жителей Страны

Басков проблем - проблему занятости.

Наконец, ни в коем случае нельзя сбрасывать со счетов роль вдохновителя Мондрагонского

эксперимента - Дона Хосе Мария Арисмендиарриета. Он воплотил в своей личности

многие своеобразные и противоречивые тенденции того времени. Католический священник,

активный участник антифранкистского движения, редактор газеты Баскской республиканской

армии, он был заочно приговорен франкистами к расстрелу и лишь чудом избежал гибели,

выдав себя за рядового солдата (список приговоренных к расстрелу, где значится

его фамилия, можно увидеть в музее МСС). Будучи сторонником доктрин христианского

социализма, Дон Хосе Мария стремился найти третий путь между капитализмом и социализмом

советского типа. В этом нашло свое отражение широкое распространение в стране

Басков различных социалистических идей. Обладая большим авторитетом одновременно

как священник и как поборник социальной справедливости, он сумел объединить вокруг

себя группу единомышленников из простых семей, которые получили при его содействии

высшее образование. Дон Хосе Мария обладал и несомненным стратегическим чутьем:

его сподвижники уверяют, что замыслы создания основных опорных структур МСС -

кооперативного банка, исследовательских кооперативов и т.д. - исходили именного

от него, хотя он не занимал никаких официальных постов в Мондрагонских кооперативах.

Однако при всей своей успешности опыт Мондрагонской кооперативной корпорации

показывает нам и ограниченность таких - пусть и крупных - островков кооперативного

движения в океане капитализма. Во-первых, это ограниченность масштабов. Помимо

МСС, в Стране Басков действуют еще сотни кооперативных предприятий, и множество

предприятий, частично принадлежащих работникам. Немало таких предприятий и в остальной

Испании. Однако, несмотря на значительную долю кооперативов в производстве отдельных

видов продукции, их удельный вес в испанской экономике в целом ничтожен.

Во-вторых, кооперативные предприятия, преодолевая капиталистический характер

экономических отношений в одних аспектах, вынужденно сохраняют его в других. В

кооперативах ликвидирован антагонизм между собственником средств производства

(капиталистом) и наемным работником. Член кооператива выступает одновременно и

как собственник, и как работник. Однако в них не ликвидирована другая основа классового

деления, связанная с общественным разделением труда и разным местом людей в общественном

процессе производства. Речь идет о противоречиях между рядовым работником и управляющим,

о сохраняющихся существенных различиях между рабочими и специалистами. Значительно

смягчив эти противоречия, найдя довольно эффективные формы компромисса между интересами

рабочих и управляющих, Мондрагонские кооперативы не смогли снять проблему полностью.

Часть этих проблем проистекает не только из технологической природы фабричной

организации труда, но и диктуется общими условиями капиталистической экономики

- менеджер должен добиваться прибыльности предприятия, обеспечивать необходимую

интенсивность и дисциплину труда, экономить на издержках производства (в том числе

и на заработной плате и на числе занятых) и т.д. Понятно, что в этих своих стремлениях

он нередко будет натыкаться на интересы рабочего, которого привлекает более свободный

режим труда и отдыха, более высокая оплата и т.д.

Отчасти компромисс между этими интересами обеспечивается в Мондрагонских кооперативах

за счет временно занятых работников. Хотя по правилам их численность не должна

превышать 10% занятых, нередко эта норма превышается. Временные рабочие получают

ту же зарплату, что и члены кооперативов, но они не участвуют в распределении

прибыли по итогам года, на них не распространяются различные гарантии и льготы,

которыми обеспечиваются члены кооперативов. Эти временные работники первыми попадают

под увольнение при неблагоприятных изменениях экономической конъюнктуры.

Не существует в Мондрагонских кооперативах и системы постоянного участия работников

в принятии хозяйственных решений на различных уровнях (подбно той, которая существует

на некоторых американских предприятиях, находящихся в собственности занятых, или

существовала в 70-е - 80-е годы на Калужском турбинном заводе), хотя элементы

производственной демократии там есть на верхнем этаже управления (общее собрание

кооператива, Генеральная Ассамблея МСС) и на низовом уровне (автономные самоуправляющиеся

бригады, кружки качества).

Такого рода противоречия и проблемы прорвались однажды в Мондрагонских кооперативах

в открытой форме - в форме забастовки 1974 года на старейшем кооперативе Ulgor.

Хотя с тех пор было предпринято немало шагов для смягчения указанных противоречий

(расширены полномочия Социального Совета, получила развитие производственная демократия

на низовом уровне), подспудное их проявление можно ощутить и сейчас.

Следует прямо сказать, что вряд ли в условиях капиталистической системы можно

было бы ожидать много большего от такого рода изолированных экспериментов. Опыт

Мондрагонских кооперативов ценен не тем, что являет собой некий идеальный образец

самоуправляющейся социально-экономической системы. Отнюдь нет - мы видим пример

реально возможного в рамках буржуазной цивилизации. Однако и этот пример показывает

нам, что даже частичные шаги в социалистическом направлении обеспечивают более

эффективное, более стабильное, более социально справедливое экономическое развитие,

оказывая благотворное влияние и на всю социальную атмосферу.

Уникальность опыта МСС не означает при этом, что практика Мондрагонских кооперативов

лежит вообще вне общего русла развития экономики участия. Многие элементы мондрагонского

опыта уже применяются кооперативным движением на Западе. Это и использование схемы

индивидуальных счетов капитала, и создание опорных структур, обеспечивающих кооперативам

финансовую поддержку, помощь и консультации в области менеджмента, финансов, маркетинга

и т.п.

Российское кооперативное движение переживает сейчас далеко не лучшие времена.

После периода "бури и натиска" 1988-1991 гг., когда под видом кооперативов

создавались в основном обычные частные фирмы, наступило похмелье. Оказалось, что

"номенклатурный", мафиозно-монополистический капитализм враждебен любому

самостоятельному предпринимательству, и не только коллективному. Кооперативы стали

лопаться один за другим или уходить в сферу торговли и спекуляций.

Сейчас реальный кооперативный сектор в России представлен в основном реорганизованными

колхозами и совхозами. И для этого сектора опыт Мондрагонских кооперативов, как

мне представляется, окажется отнюдь не лишним. Разве не стоит для них проблема

финансирования и задолженности? Разве не стоит проблема организации снабжения

и сбыта? Думается, что объединение усилий наших сельскохозяйственных кооперативов

в таких областях, как создание общей банковской структуры, совместной сети сбыта

продукции, общей системы снабжения семенами, удобрениями, техникой, горючим, совместной

ветеринарной службы, может стать для них большим подспорьем в борьбе за выход

из кризиса. Да и многие внутренние проблемы Мондрагонских кооперативов, как и

борьба за их решение, содержат для нас немало полезных уроков, как частного практического

свойства, так и таких, которые подталкивают к теоретическим обобщениям.

И главным среди этих обобщений мне видится тезис, высказанный уже очень давно

- что для подлинного успеха кооперативного движения, делающего его способным действительно

преобразовать экономическую систему современного общества, кооперативный труд

должен развиваться в общенациональном масштабе и на общенациональные средства.

См. также: Колганов А. И. Коллективная собственность и коллективное предпринимательство.

М., Экономическая демократия, 1993; Боуман Э., Стоун Р. Рабочая собственность

(Мондрагонская модель): ловушка или путь в будущее? М., то же, 1994; Ракитская

Г. Миф левых о Мондрагоне //Альтернативы, № 2, 1996, стр. 104 - 118

MONDRAGУN'S ANSWERS TO UTOPIA'S PROBLEMS*

Kenneth R. Hoover

Professor of Political Science

Western Washington University

"We are not working for chimerical ideals. We are realists. Conscious

of what we can and cannot do [...] we concentrate on those things that we have

hopes of changing among ourselves more than on those things that we cannot change

in others [...] Dedicated to changing those things we can and that we are in fact

changing, we are conscious of the force that this movement produces."

Fr. Josй Arizmendiarrieta

ABSTRACT

After a brief historical overview, the discussion centers on the ways that

the Mondragуn cooperative network has dealt with some classic problems of utopian

communities: 1) capital formation, 2) charismatic leadership, 3) responses to

economic cycles, 4) differences in the interests of workers and managers, 5) the

role of automation and technology, 6) the encouragement of entrepreneurship, and,

finally, 7) socialization to the cooperative ideal. The analysis of the responses

to these challenges is based on the research literature on Mondragуn, as well

as on discussions with scholars and experts who have studied the system and with

key individuals in the Mondragуn network. The conclusion suggests some of the

remaining challenges and an agenda for further research.

CITATION: Hoover, Kenneth R. , "Mondragon's Answers to Utopia's Problems,"

Utopian Studies 3 (1992) 2, 1-19.

The allure of utopian visions is in the prospect of surmounting the difficulties

that bedevil daily existence. As Frederic White observes, "It is this inspired

disgust with things as they are that creates the literature of Utopia" (1981,

viii). Yet nothing reveals the nature of these difficulties so clearly as various

efforts to practice utopian ideals. The problems utopias encounter fill the concluding

chapters of histories of utopian communities, provide the stuff of realist rejoinders

to reformist proposals, and become the central theme of prominent dystopias such

as Brave New World, and 1984.

The literature of utopia offers a critique of the failures of society, but

it is a critique that itself can be analyzed to reveal the truly intractable elements

of life's difficulties, as opposed to the possibilities for constructive change.

The analysis offered here sets some of the classic problems of utopias against

the experience of the Mondragуn cooperatives, a highly successful network that

has achieved some of the principal goals utopias strive for.

My plan is to review briefly the history of the Mondragуn cooperatives and

the record of their performance, then to identify a few of the problems utopian

communities commonly face, and finally to suggest some of the ways that the Mondragуn

cooperatives have avoided and, in some cases, met these challenges over the last

thirty-five years. In the conclusion, I will point to the unsolved problems that

remain for Mondragуn, and to an agenda for further research. The discussion is

based on interviews with several Mondragуn participants as well as with researchers

working on the topic, and on the cross-disciplinary literature that has been developing

steadily as the "experiment" has become institutionalized.

Background

First, what is Mondragуn? The name identifies a community in northern Spain

of about 28,000 located south and east of Bilbao among the valleys and small mountains

of Guipuzcoa province. Mondragуn is the center of a network of more than 100 employee-

owned cooperatives, including Spain's largest appliance manufacturer, and its

sole producer of micro-chips. The network spreads through towns and villages across

the three provinces of the Basque country.

The performance of the Mondragуn cooperatives over the last three decades has

attracted international attention. For example, it was reported recently in The

Economist that:

"With sales in 1988 of Ptas 205 billion ($1.8 billion), a workforce of

22,000 and output equal to 4% of the region's GDP, the Mondragуn group ranks among

Europe's industrial heavyweights... . It sets out not to earn dividends for shareholders

but to provide jobs, social security, and education. Through fair weather and

foul, it has done so." (Anon., 61)

A brief overview of the Mondragуn experiment may be useful. There are four

periods to the development of the "Mondragуn Cooperative Experience":

the establishment of a technical school by Fr. Josй Maria Arizmendiarrieta in

1943, the development of the first cooperative in 1956 followed by rapid growth,

the recession period beginning in 1979 which saw unemployment reach 25% in the

surrounding areas, and the present phase which began with full recovery of the

cooperatives in 1986. Currently, the cooperatives have positioned their resources

for the level of competition attendant upon the 1992 dismantling of tariff barriers

within Europe.

At the heart of the Mondragуn network is a consortium of cooperatives in the

kitchen products field marketed under the brand-name FAGOR. The FAGOR consortium

is the direct descendant of the first industrial coop named Ulgor, a name composed

of the first letters of the names of the five young engineers who founded it in

1956. These five were all students of a priest, Fr. Josй Arizmendiarrieta, whose

interest in improving the lives of his parishioners took concrete form with the

creation of a technical school in Mondragуn in 1943. This was the first step in

the creation of an innovation in political economy.

Fr. Arizmendiarietta combined many qualities according to observers: he was

a deft teacher, an inspirational figure, as well as a very practical person who

guided the movement without institutionalizing his power (Whyte and Whyte, 223-254;

Meek and Woodworth). Making a self-conscious attempt to navigate a course between

the principles of Adam Smith and Karl Marx, he found his basic texts in a combination

of Catholic moral teaching on the economy and the experience of the 19th century

utopian cooperative experiment at Rochdale in England.

The priest remained in the role of teacher, rather than administrator, though

occasionally he took direct action to assist the movement. In one instance, he

persuaded the directors of ULGOR to create the cooperative bank as a solution

to their financing problems. In another, he launched the concept of a working

technical cooperative as an adjunct of the polytechnical training school. In both

cases, he worked through study groups and endless consultations, while becoming

a knowledgeable interpreter of Spanish legal and bureaucratic requirements (Meek

and Woodworth, 1991, 519). He was not an overtly charismatic leader, but he clearly

had a talent for synthesizing theory and practice in response to the needs of

the moment. Father Arizmendiarrieta died in 1976.

The cooperatives are based on the principles of England's Rochdale Pioneers.

Each member, upon being hired to work in a cooperative, loans a set amount to

the cooperative's capital fund, for which he or she receives a fixed rate of interest.

Compensation takes three forms: wages, 6% fixed interest on the capital loan,

and profits of the cooperative which accrue to shares and are used for capital

investment until the member's retirement. Wages are set at the entry level by

the prevailing labor market, and constrained by the general principle of a 6:1

ratio between highest and lowest wages. The ratio was initially established at

3:1. With the increasing sophistication of technical and managerial skills required

to sustain a competitive industrial position, the ratio was raised to 4.5:1, and

in 1987 to the present level (Whyte and Whyte, 1991, 44-45). The initial capital

loan contribution can be financed on credit through the bank for a specified period

of time.

The administration of the cooperatives follows a pattern. Managers are appointed

for a term, usually four years, by an elected Supervisory Board which is accountable

to the General Assembly of all cooperative members. Thus there is indirect accountability,

an approach that allows for some latitude on the part of managers as they pursue

the economic and social objectives of the cooperatives. A second elected body,

the Social Council, deals with the concerns of members "as workers,"

rather than "as co-owners" in the way that the supervisory board does.

The management is accountable primarily to the latter, though it obviously has

to work with the former as well (Whyte and Whyte, 213).

There are several features of the Mondragуn network that are distinctive, and

perhaps the most important are the secondary institutions that tie the whole network

together. Chief among them is the bank. All of the cooperatives participate in

the bank: it is their creature in a sense, though it has grown to become one of

Spain's most significant financial institutions. This ingenious institution provides

a source of capital and, just as important, of expert advice and planning assistance

for the member coops. The agreement that is the instrument of membership in the

bank is, in effect, the constitution of the Mondragуn network. The agreement sets

overall limits on pay ratios, the basic parameters of compensation, and many other

aspects of policy.

The elaborate system of secondary cooperatives includes a health and pension

system, a research institute that investigates new technological applications,

an educational system covering all grades through to a technical university that

is itself a producing cooperative, and an impresarial division that focuses in

the start-up of new cooperatives. All are governed by boards held accountable

to the member coops, as well as to their own working share-holders.

One distinctive feature that must be accounted for is the relationship with

the Basque nationalist movement. This link is important for historical reasons,

and a critical element in determining the transferability of the Mondragуn experience.

It is very nearly impossible to reach a simple conclusion about this because of

the many paradoxes presented by the cultural environment. There is a long history

of cooperative efforts in the Basque country; yet there is also a history of bitter

competition and political rivalry. Nationalist sentiment is strong and there is

reportedly substantial support among Mondragуn participants for Herri Batasuna

(a coalition of pro-Basque groups including the terrorist ETA), and the ETA itself.

At the same time, the hiring policy is non-exclusionary and the coops do not engage

directly in political activity. The coops were born in a period of adversity and

persecution by the Franco regime, yet they have survived in a period of relative

affluence in post-Franco Spain. The school system teaches the Basque language

and emphasizes nationalist values, however more than a quarter of the cooperative's

business is in international trade, and its products are widely marketed throughout

Spain.

The best indicator as to whether the Basque factor is essential to the success

of this form of production is to see if similarly successful efforts can be found

elsewhere. The evidence shows that the cooperative sector in capitalist societies

is much larger than most people realize. (Estrin and Jones; Ben-ner) While direct

efforts to imitate Mondragуn have had mixed results, the reasons for the failures

show patterns that can be dissociated from cultural factors. Perhaps the aspect

of the Basque connection that is the most important is the incentive nationalism

provides for establishing a thoroughgoing educational system that stresses values

congenial to the cooperatives (Meek and Woodworth, 523). The question of transferability

will receive further consideration as we analyze the approaches taken to the classic

problems of utopias.

THE RECORD

An analysis of the Mondragуn cooperative experience must be set against the

background of its remarkable economic performance. In the first twenty years,

more than 15,000 jobs were created (Thomas and Logan, 9). The growth rate in the

1976-1983 was four times that of Spain's industrial output generally (Bradley

and Gelb, 1987, 84). In the decade from 1976 through the recession until 1986,

150,000 jobs were lost in the Basque country while Mondragуn created 4,200 new

jobs and left none of its members without employment or assistance.

Furthermore, by the range of products manufactured, the network has demonstrated

that cooperatives can successfully compete across nearly the entire range of the

economy. The most surprising aspect of the list of products is how many rely on

high technology. Cooperatives have an image as service-related organizations,

however the Mondragуn experience is that the system works better in association

with forms of highly organized production.

The achievements of the Mondragуn cooperatives are numerous, significant, and

increasingly well-documented by scholars from several nations. The cooperatives

are more productive than comparable capitalist firms, and have absentee rates

that are 50% lower (Thomas and Logan,, 50-51). Well organized cooperatives generally

seem to have a stronger ability than conventional firms to survive and even prosper

during recessions and downturns (Ben-ner, 22). Keith Bradley suggests that state

policies favorable to worker-owned firms are more likely to produce solid economic

results than interventionist strategies designed to shore up or subsidize conventional

firms ( 51-71). In the case of Mondragуn, as much as a third of the production

of some cooperatives is exported, and this is where the growth is for most product

lines.

All of these economic benefits are in addition to the advantages to the workers

of participating in a system where information is accessible, where there is a

genuine commitment to providing a reasonable level of security for workers and

their families, and where there is the real prospect of increasing community educational

standards, health, cultural participation, and wealth itself.

Rather than reducing human labor to the status of a commodity in the marketplace,

the cooperatives use markets to provide the critical information necessary to

plan for the security of workers. Mondragуn has come to represent a major new

"social invention," in the phrase of William Foote Whyte and Kathleen

Whyte -- one that many would say has vindicated those who have labored in the

utopian vineyard down through the centuries. But is it a utopia? A partial response

to that question lies in appreciating Mondragуn's answers to utopia's problems.

UTOPIA'S PROBLEMS

One common scenario found in historical accounts of utopian communities unfolds

as follows: the hopeful beginning, early struggles, a fruition of effort that

bears the seeds of destruction, and a sober conclusion with lessons drawn as to

the weakness of leaders, the perversity of followers, and the folly of planned

communities The less pessimistic histories draw further lessons about the good

effects of efforts at designed communities and the sense in which they point the

way toward reforms of society generally.

There is a chronic aspect to the problems that are revealed in utopian experiments,

and it is these symptoms of dystopia in the heart of utopia that I want to focus

on. If there is a clinical metaphor here, our purpose is to understand the forms

of preventive medicine, therapy, and intervention that have kept Mondragуn healthy

through more than thirty years of changing conditions.

A number of classic problems need not be discussed in any detail since they

do not apply to the case of Mondragуn. The problem of economic isolation generated

by differences between the internal and external systems of economic exchange

does not arise because Mondragуn operates as a business in the marketplace, rather

than as a fully self-sufficient set of communes.

The familiar difficulty of disappointed expectations has been minimized since

Mondragуn was founded in adversity, and has never aimed to offer a complete recipe

for human happiness. The focus has been on economic security, with attention given

to the forms of socialization required to achieve it. Mondragуn has not challenged

the mores and customs prevailing in Basque society except insofar as they limit

economic modernization. There is a political agenda related to Basque nationalism,

however the network has a non-exclusionary hiring policy.

On the other hand, the significant issues that have been dealt with include:

1) capital formation, 2) charismatic leadership, 3) responses to economic cycles,

4) differences in the interests of workers and managers, 5) the role of automation

and technology, 6) the encouragement of entrepreneurship, and, finally, 7) socialization

to the cooperative ideal. Each of these has had fatal consequences for previous

efforts at the establishment of utopian communities; and each has been the subject

of careful attention at Mondragуn.

Capital

Capital formation is a fundamental weakness of cooperatives historically. Modern

requirements for technological modernization exacerbate the problem. Furthermore,

the need for capital investment sets off a conflict between compensation for labor,

on the one hand, and investment in machinery, on the other.

In the latter part of the 19th century, Sidney and Beatrice Webb argued that

this was reason enough for the Fabian Society to turn toward statist solutions

to the evils of capitalism (Thornley, 27). On the contemporary scene, problems

of capital investment pose the principal threat to the continuation of the Israeli

kibbutzim. In a time of rising inflation, Israeli collectives engaged in speculative

forms of investment using generous government credits. These credits reduced the

need for discipline with respect to the trade-off between labor compensation and

investment requirements. With the subsequent explosion of interest rates, a heavy

debt burden has imperiled numerous kibbutzim (Brooks, A20).

Perhaps the most innovative aspect of the Mondragуn cooperatives is the creation

of a banking system, named the Caha Laboral Popular (CLP), that works diligently

at providing capital, monitoring performance, and planning new cooperatives. Founded

at the initiative of Fr. Arizmendiarrieta in 1960, it is now the 15th largest

bank in Spain (Anon., 61). It has several hundred thousand depositors, over $2

billion in assets, and more than 200 branches (Lutz and Lux, 263).

As a secondary cooperative, the Caha Laboral Popular is tied closely to the

welfare of the network. The bank's board is made up of two-thirds representatives

from the other cooperatives and one-third from the employees of the bank (the

Social Council is elected by employees only). Compensation to the employees is

in part dependent on the overall performance of the cooperative network. The Caha

makes about 80% of its loans outside the network since the number of profitable

opportunities for investment within the system is limited, however the profits

are used to the advantage of the member cooperatives.

The initial success of the bank had to do with a law that permitted cooperative

banks to pay 1/2% higher interest than regular banks, an advantage that contributed

to a dramatic rise in deposits. If there is one area where state intervention

may play a useful role in facilitating cooperative development, it is in providing

an advantage for cooperative banks. The public receives in return the benefits

that come from the creation of stable jobs that contribute to durable communities.

Coops avoid the social costs of capitalist firms. They are far less likely to

be bought out, or dealt with as exploitable property, than are conventional firms.

Both the treatment of workers, and the treatment of the community by the cooperatives,

offer substantial public benefits.

The centrality of the bank is underscored by the significance of the "contract

of association" that all members must hold to. By refining the contract over

time, the experience of the cooperatives has been given practical form. If there

is a constitution to Mondragуn, this is it. Everything from ratios of pay, to

the organization of authority, to external audit arrangements, to non-discriminatory

employment policies are specified. The bank retains the right to intervene in

failing cooperatives and has done so with dramatic results in several cases (Whyte

and Whyte, 68-88).

The arrangements for using capital have become a principal strength of the

Mondragуn cooperatives rather than, as with the Rochdale experiment, a source

of weakness. The challenge of capital formation will be put to the supreme test,

however, as Mondragуn faces up to the difficulties of competing with the major

corporations of the European Community without tariff protection in post-1992

Europe. Currently experiments are under way with holding companies and joint ventures

formed with conventional firms as a way of accessing international markets.

Charismatic Leadership

For all of the impressive social and economic machinery of Mondragуn, there

is a factor of leadership that must be accounted for. Fr. Arizmendiarrieta died

in 1976; Mondragуn is still alive and well 13 years and many severe challenges

later. He was not, in any event, a domineering figure. Indeed, he preserved his

role as teacher and guiding spirit while avoiding an active role in, for example,

Mondragуn's one major labor dispute (Whyte and Whyte, 96-102).

Three of the founding five students of Fr. Arizmendiarrieta are still active

in the cooperative, one in FAGOR as its international director, Sr. Jesus Larraсaga,

whom we were able to interview. The other two, Sr. Ormaechea and Sr. Gorroсogoitia,

served as heads of the cooperative banking system that now plays a powerful role

in assuring the fiscal integrity of the cooperatives. While the departure of the

founders will be clearly noticed, it is apparent that there has been substantial

executive talent recruited from within as well as brought in from outside. Several

outsiders have provided major leadership skills during periods of change and crisis

(Whyte and Whyte, 113-127).

However, it must be said that the visitor senses that some of the cooperative

zeal has dissipated with the passing of Fr. Arizmendi. Judging from interviews

with participants, there is some concern that this has weakened the cooperative

spirit. The necessity for laying down a firm educational base as the first condition

of successful cooperative life is the key element that concerns activists in the

Mondragуn network. As Meeks and Woodworth have suggested in their work on the

centrality of education to the Mondragуn experience, both ideological and technical

training are critical to the success of cooperatives (Meek and Woodworth). There

are many cases where the former has been tried without the latter, and cooperatives

have often failed for lack of participants who have the requisite technical skills.

For Mondragуn, the challenge may be the reverse. The polytechnical college

is now one of Spain's most prestigious schools. The question is whether, in the

absence of the socialization provided by the first wave of leaders and activists,

the ideological dimension of cooperative socialization will be sufficiently dealt

with.

Thus the impression at this stage is that the technical leadership is in place

to deal with economic decisions; though there is less certainty about the exercise

of leadership in the socialization and education functions associated with Mondragуn.

Perhaps the organization of a highly successful schooling system has put in place

a process that is self-renewing independently of charismatic leadership, however

there is no reliable evidence available on this point.

Cycles in the Economy

For the first two decades of Mondragуn's existence, there was little outside

attention paid to it. Partly as a matter of survival in Franco's Spain, the coops

did not invite notoriety. For those who were inclined to notice the experiment,

the Basque cultural factor may have seemed to render it unique and therefore of

little interest as a generalizable experience.

What really attracted international attention was the ability of the coops

to survive a major depression in the Basque economy. Western nations in the late

seventies and early eighties experienced huge dislocations in their industrial

economies. The successful adaptation to these adversities at Mondragуn contrasted

sharply with the dislocation and despair found in other European and American

industrial centers was startling indeed.

Economists began to look systematically at the cyclical adaptation of Mondragуn

in comparison with Basque capitalist firms, and to relate that data to the comparative

performance of cooperatives in other European countries. The comparative performance

of Mondragуn was amazing; that of other cooperatives was, at the very least, impressive.

Both forms of analysis yielded generalizations that could be applied to cooperatives

generally, while diminishing the significance of the cultural factor in particular.

(Bradley and Gelb, 1982, 1987; Whyte and Whyte, 129-222)

What emerges generally is that worker-owned firms have a lower likelihood of

failure in downturns than capitalist firms, and they distribute the costs of recession

far more equitably among the stake-holders in the business. The peril for worker-owned

firms occurs, paradoxically, in prosperity when there is a tendency for some cooperatives

to respond to immediate economic incentives by hiring non-members as workers in

order to reduce both labor costs and long-term commitments to job security (Ben-ner,

26; Bradley and Gelb, 1982, 30-31). Over the long term, cooperatives may be in

more danger of dissolution on the upside of a cycle than the downside. While this

is the pattern for European cooperatives generally, Mondragуn appears to have

benefitted from the downside strengths without succumbing to the upside threats

to its integrity as a cooperative network.

Perhaps the most important factor in avoiding this development is the pro-active

stance toward job creation through the expansion of membership rather than temporary

labor. It is a condition of the contract with the Caha Laboral Popular that cooperatives

will undertake membership expansion when market opportunities are present and

capital is available.

It is also true that the cooperatives are situated in small communities where

limited mobility makes transient labor less available and desirable. So far the

rule that non-members may not be hired other than as a very small percentage of

employment has held.

The semi-isolated situation of the Mondragуn cooperatives probably contributes

another element to their stability by reducing labor turn-over. This has the effect

of reducing training costs, and preventing the loss of equity capital. The labor

market of these cooperatives, both for locational and cultural reasons, is somewhat

separated from the national labor market which, in turn, makes it possible to

operate with constraints on wages and particularly on managerial salaries that

would be much less acceptable in a major urban area.

Diversification of risk is another major advantage of the Mondragуn network.

The wide array of products manufactured, and the dispersion of manufacturing through

a variety of units, means that risks from market failure as well as management

failure are minimized. Correspondingly, the ability to adjust through labor transfers,

and to avoid management failures by close monitoring and careful counseling through

the bank, makes successful adjustment far more likely.

The fact that Mondragуn came through a recessionary period comparable in severity

to a U.S. depression with virtually no real unemployment in the cooperatives is

evidence for this extraordinary adaptive ability. What remains to be seen is how

the cooperatives adapt to a new wave of prosperity in the context of a challenge

from the European Community in 1992.

Differing Interests of Workers and Managers

The divergence of interests between managers and workers is built in to the

foundation of the industrial system. It accounts not alone for the failure of

cooperatives, but of capitalist firms as well. Indeed, much of the overhead cost

of management in capitalist firms is devoted to dealing with the problems of motivation,

productivity, absenteeism, stress, and turn-over attributable in large part to

the human inefficiencies of this critical relationship.

Cooperatives generate expectations that such differences will be minimized;

indeed that is the rationale for their existence. The classic error of cooperatives

is to presume that democratic decision-making alone can address the problem. Mondragуn's

constantly evolving system for minimizing class conflict is thus far a successful

response to the problem as evidenced by the perceptions of participants. In a

systematic survey in 1980, Bradley and Gelb report that "only 18 percent

of co-operateurs perceived a substantial social divide (between workers and managers);

45 percent saw no division at all. (Bradley and Gelb, 1981, 221).

Beneath the question of social divisions lie the hard realities of divergent

economic interests. The whole logic of the Mondragуn's institutional framework

is that management must be constrained to operate in the interest of the security

of the members. It is management's job to reconcile security with the marketplace,

rather than to maximize profits for absentee owners at the expense of labor. At

Mondragуn workers are rewarded for performance through increased financial security,

and protected against arbitrary personnel management through carefully developed

systems of representation and accountability.

The 6:1 pay ratio, the term of appointment for managers, and the formal representation

of workers through the Supervisory Board and the Social Council establish parameters

for the reconciliation of interests. The ethos of cooperation and the peer pressure

for performance in a system of shared benefit from productivity sustain the cooperative

mode of behavior.

There are limits to the success of participation as a key to reducing worker-management

differences in Mondragуn however. The Whytes report that reactive participation

is very high in Mondragуn. Workers have many opportunities to respond efficaciously

to management proposals for changes in working situations. However pro-active

participation is not as great as in some of the most advanced capitalist firms

where workers may be involved from the beginning in job design. Most of the job

redesign in the Mondragуn cooperatives has been management-initiated and has been

slower to catch on than might otherwise have been the case (Whyte and Whyte, 210-211).

The growth of pro-active participation, one may speculate, has been limited

first by the origins of the cooperatives in a poor area characterized by minimal

education. The job redesign initiatives came with prosperity in the seventies.

However they took second place to concerns for employment preservation in the

face of recession. Now, with stability restored, there is new interest. However,

again, a larger issue looms which is adaptation to the realities of European Community

competition in an increasingly open environment. It is likely that further advances

in this area await a period of stability and perhaps the incorporation of a new

generation of better educated young workers who will wish to advance the agenda

of humanizing work.

Automation and Technology

Cooperatives are often associated with service enterprises, and occasionally

with resistance to technology. This resistance has roots in history as well as

in the practical dimensions of these experiments. One root of the cooperative

movement is found in the old craftsmen's guilds (Thornley, 26-29). The antipathy

to technology arose out of rearguard actions against the arrival of industrialization

and, finally, the systematization and schematization of blue collar work in the

form of Taylorism.

Mondragуn represents an adaptation of Taylorism, and a rebellion against the

managerial domination of the personal lives of working people known as Fordism

(Meyer). An illustration is the response in the cooperatives to automation. FAGOR,

the largest and most significant Mondragуn cooperative, operates Spain's most

automated assembly line for producing refrigerators. Due to the sophistication

of the machine tools, some of which were designed in the coops, four different

models of refrigerators can move through the line simultaneously. As another example,

EROSKI, the consumer cooperative associated with Mondragуn, has developed an automated

warehouse with computer-driven forklifts.

Rather than avoiding automation, the Mondragуn cooperatives have defined the

"problem" of automation as a matter of obtaining control over the benefits

of technology on behalf of members. The dilemma posed by automation for job creation,

a central social goal of the network, has been faced. The objective has not been

to preserve every job at any cost, but rather to preserve the security of member's

positions through the best use of technology. It is a system that treats direct

labor as a "semi-fixed cost" similar to the treatment generally accorded

to the cost of machinery and facilities, and often to indirect costs and managerial

labor. Changes in demand are dealt with through burden-sharing and phased change.

In conventional firms, Fordism was a system of social control over workers

aimed at reducing the behavioral problems involved in harnessing human labor to

machine paced production. The conflict of interest between the laborer and his

mechanical pace-setter was resolved through discipline, incentives, and manipulation.

In the Mondragуn network, not all of these problems are resolved -- and there

are still complaints about the monotony of factory work. However, the monetary

benefits of technology accrue directly to the accounts of workers. Furthermore

there are extensive facilities for adjustment and re-orientation as work processes

change.

There is, finally, an element of Taylorism that cannot be eliminated in modern

industrial production. Mondragуn has met that challenge in two ways: amelioration

of the worst aspects of assembly line work, and redesign of the work process itself.

In the refrigerator factory, the assembly process is integrated with rest areas

that have green plants, work stations where employees can provide their own decorations,

and a community bulletin board that contains all of the financial data about the

coop and an invitation to the free expression of ideas.

In the COPRECI cooperatives where electronic components are the main product,

work redesign experiments have been underway for the last fifteen years. One technique

is to install tables where groups of workers build components in teams instead

of working at assembly lines. Production is converted from a function base to

a product base. Rather than being harnessed to functional processes with no immediate

connection to a finished result, workers are now brought directly into a relationship

with the end product. This led to many salutary effects for motivation, cost-reduction,

product improvement, and adaptability to customer's needs (Whyte and Whyte, 118-127).

Beyond revising the process of production, it is becoming apparent that technology

and cooperatives have an interactive relationship that is the reverse of what

one might have expected. While cooperatives are often associated with labor-intensive

service operations, the literature on cooperative success factors now recognizes

that these may be the most difficult forms of cooperative venture. Technology

seems to bring to the work-place a self-evident need for order and discipline

that helps to objectify sources of conflict in the workplace so that they can

be dealt with through the techniques of democratic consultation combined with

economic rationality.

Entrepreneurship

The monastery is the utopia of the virtuous. Nineteenth century communal visions,

including Marx's, envision a utopia of the creative (Geoghegan). The liberation

of the creative instincts of the individual rose to prominence as a utopian ideal

with the decline of feudalism and, with it, the diminution of monasticism and

chivalry (Hirschman).

Yet, paradoxically, it is the entrepreneurial form of creativity that appears

to be missing from many contemporary visions of utopia, and the communities they

have spawned. It may be the attachment of the utopian tradition to arcadia and

to the guild society of craftsmen that condemns it to commercial conservatism,

but there is a distinctly reactionary style to most socialist utopian visions

of economic life. Creativity is good, but commercial entrepreneurialism, particularly

if it involves technology, is eschewed.

Whatever its relationship to utopian visions, the problem of entrepreneurial

innovation is a practical issue for cooperatives. The tendency to stay with successful

patterns of production is very strong when the security of one's share is a constant

concern. The known product is a temptation for both capitalists and the members

of cooperatives. Mondragуn's answer is to institutionalize the entrepreneurial

function.

Originally, it was the Caha Laboral Popular that took on the function of identifying

new products and advancing the formation of additional cooperatives. Working with

Ikerlan, the secondary cooperative that specializes in research, planners from

the bank facilitated product innovation at existing cooperatives and promoted

new initiatives. Ikerlan operates as a research institute with clients in many

fields of production technology, both within and outside of the Mondragуn cooperatives.

It serves the purpose of linking the network to the latest trends in research-based

product innovation.

Concern over the growing power of the bank led to the formation of a separate

impresarial division which has just recently become an independent cooperative

answerable to the governing council (Cornforth). While the imagery of entrepreneurialism

is individualist in the mythology of capitalism, the practice is very often corporate.

Mondragуn is no different in that respect.

The Impresarial Division works with Ikasbide, an educational conference center,

and Alecoop, the cooperative of the technological university, to bring together

new ideas and shape them into commercial concepts. The adaption to the recession

in the past decade was aided immeasurably by the forward-looking activities of

this research and development center.

Socialization and the Maintenance of Community

The renewal of socialization after the first generation of cooperative development

is, of course, the critical test for utopian communities. It is a little too early

to tell what the result will be in the Mondragуn network. Given the fact that

Mondragуn represents a less than comprehensive attempt at community, and one that

fits into many of the conventions of the market economy, the burden placed on

socialization is lower than for other experiments.

If we take as a benchmark for understanding the role of socialization Rosabeth

Moss Kanter's six "commitment mechanisms" (1972), Mondragуn relies on

five of them to one degree or another: communion in terms of a group ideal is

symbolically present, though membership is open to all and structured in terms

of substantive individual incentives. What is perhaps instructive is that so much

could be accomplished in the Mondragуn system with so little overt emphasis on

the expressive forms of solidarity. Investment is tangible in the form of a share

purchased and the cumulative savings that accrue over the years.

Renunciation of the outside world is a factor principally for those committed

to Basque nationalism and its indirect affiliation with Mondragуn, though there

are many other ways to express this commitment in Basque society. Another kind

of renunciation may be found in the experience of those at the top of the pay

scale in Mondragуn who could be earning more money, and achieving higher relative

status, for similar work in the conventional economy. For these people, renunciation

of the materialist status heirarchy of the conventional economy comes with acceptance

of the alternative values of security, stability, and harmony that are found within

the cooperative system.

Sacrifice was an early aspect of the experience, and a factor of renewed significance

during the recession when some cooperatives voluntarily reduced wages rather than

eliminating jobs. This form of sacrifice is the clearest indication that the bonds

forged in the Mondragуn system are indeed strong. The transcendence of everyday

experience through charismatic leadership is of a low order in Mondragуn. The

remaining device, mortification, really has no place in this instance.

While Mondragуn fits in these respects with the general profile of utopian

communities, perhaps the success of Mondragуn lies in not having over-estimated

the level of community that could be achieved in a modern industrial economy.

Differences of degree are important. Mondragуn, for all of its accomplishments,

has presented a lower order of challenge to its socio-economic environment than

most utopian communities.

There are critics who have pointed out that Mondragуn does not go far enough.

Some feminists have criticized the cooperatives for not having moved more quickly

and decisively to improve the position of women. Hacker, for example, attributes

the limitations on the progress of women at Mondrag n to its common roots with

capitalist firms in "militarist and patriarchal" forms of development.

There is, on the other hand, a successful women's cooperative, and women are present

in all phases of the network's activities in significantly higher percentages

than in comparable Basque industries (Whyte and Whyte, 75-78).

Absent the pressure exerted by the EC's transformation in 1992, the socialization

factor might not be so critical. The educational system associated with Mondragуn

might be sufficient to reproduce the conditions for its maintenance. However both

the level of material expectations and of market performance demanded by burgeoning

world competition place fresh strains on the Mondragуn cooperative experience.

It remains to be seen if the network is equal to this new challenge.

CONCLUSIONS

Is this a utopia at all, or is it, to adapt a phrase from Sir Thomas More,

"a fiction whereby the [capitalist] truth, as if smeared with honey, might

a little more pleasantly slide into men's minds?" (In Kumar, 24). Certainly

there are skeptics on the left, Edward Greenberg principal among them, who fear

that cooperatives may well become a form of "collective capitalism."

My own conclusion is that Mondragуn does indeed combine elements of the utopias

of Marx and Smith. Scarcity is overcome in an environment where the humanization

of the labor process can at least be attempted, and Marx might have settled for

that if he had seen the 20th century results of other avenues towards his utopia

(cf. Hoover and Plant).

Adam Smith had a utopian vision as well. He conceived of industrious individuals

increasing the social product through rational investment of their energies and

capital. Smith defended his utopia against the accusation that it enshrined avarice

by pointing out that the self-discipline engendered by the marketplace would provide

a larger moral dividend than any attempt at altruistic preaching on behalf of

"moral sentiments" (Hirschman).

In Mondragуn self-interest is indeed harnessed to the increase of the material

product of the society, but the link is through a cooperative system that guards

against abuse and exploitation. The reward to self-interest is made more secure

and comprehensive by the functioning of the secondary cooperatives, and they,

at the same time, give to the community an institutional claim to moral achievement

that is considerably more secure than Smith's proposition about the ability of

vanity somehow to discipline lust and avarice.

While there may be no intrinsic reason why a cooperative as opposed to a capitalist

firm would behave in a more socially responsible fashion toward, for example,

the environment, the conditions for prudence and long term vision are clearly

in place. Absentee ownership, mobile labor, the treatment of products and facilities

as speculative property all conduce to bottom-line short term thinking of a kind

that is quite obviously dangerous to the rhythms and continuities that familial,

social, and ecological survival require. Mondragуn has demonstrated this by generating

its own social institutions and setting aside a fixed percentage of profits for

community improvement. The relative performance of capitalist and cooperative

firms in this region on environmental issues would make an interesting research

project.

Beyond cooperative housing developments and the educational system, communal

life styles are not, however, part of the experiment. Clearly it is not a liberationist

utopia on the Freudian model of Norman O. Brown, Herbert Marcuse, or Charles Reich

(Kumar, 401-402). Mondragуn attempts to build a kind of middle class familial

utopia that carries its own benefits for the personal life, as well as the life

of the community. Mondragуn can claim to provide the basis for family life through

its cooperative housing developments, educational system, social agencies, and

health programs.

The problem with assessing this aspect of Mondragуn is that virtually all of

the research thus far has concentrated on its economic and political characteristics.

It would be fascinating to know how the life of the Mondragуn member differs from

that of other citizens with respect to social interactions, educational experiences,

recreation, and family life. Research on these cultural and socio-psychological

questions remains to be done. A fascinating project awaits.

Hopefully, inquiry of this sort will be an extension of the research model

presently in place. Through a partnership between Mondragуn and Cornell University,

a "participative action research" team has been developing new studies

that grow out of a meeting of the minds between participants in Mondragуn and

skilled social scientists experienced in labor and industrial relations. Independently

of its association with Mondragуn, the research model needs to be considered as

a pathbreaking attempt at resolving the tension between values and positivist

analysis in modern social science (Whyte, Greenwood, Lazes, 5; Whyte, 1982; Hoover,

138-144).

Participative action research is linked in the Mondragуn case to the task of

creating a "social invention," to use another of William Foote Whyte's

evocative phrases. Thus the meaning of Mondragуn for academicians may well be

that it is the harbinger of a new social science -- one that brings together the

implicit agenda of social science, which is the improvement of human society,

and the appropriate tools and strategies for analysis in an experiment with great

significance for the future of the industrial world.

While there is surely more to be known about Mondragуn, it is apparent that

by adopting a rather modest and straightforward approach to the classic problems

of utopia, it has achieved far more than thousands of other experiments. This

record of durability suggests that it may even be able to compete successfully

in the new world of global competition, while retaining important elements of

the cooperative ideal.

REFERENCES

Anon. (1989), "Co-operate and Prosper," The Economist, April 1, 1989,

p. 61.

Ben-ner, Avner (1988), "Comparative Empirical Observations of Worker-Owned

and Capitalist Firms," International Journal of Industrial Organizations,

6, pp. 7-31.

Benham, Lee, and Philip Keefer (1986), "How Diverse Organizations Survive:

A Case Study of the Mondragуn Cooperatives," Working Paper No. 100, May,

1986, Center for the Study of American Business, Washington University, St. Louis,

MO.

Bradley, Keith, and Alan Gelb (1981), "Motivation and Control in the Mondragуn

Experiment," British Journal of Industrial Relations, 19, 2, pp. 221.

Bradley, Keith (1986), "Employee Ownership and Economic Decline in Western

Industrial Democracies," Journal of Management Studies, 23 (January, 1986),

pp. 51-71.

Bradley, Keith, and Alan Gelb (1982), "The Replicability and February

28, 1992 Mondragуn Experiment," British Journal of Industrial Relations,

20 (1982) 1, pp. 20-33.

Bradley, Keith, and Alan Gelb (1987), "Cooperative Labour February 28,

1992 Response to Recession," British Journal of Industrial Relations, 25

(March) 1, pp. 77-97.

Brooks, Geraldine (1989), "The Israeli Kibbutz Takes a Capitalist Tack

to Keep Socialist Ideals: Collectives Are Deep in Debt But Find Innovative Ways

to Serve Common Good," Wall Street Journal, Sept. 21, 1, A20.

Cornforth, Chris, "Can Entrepreneurship Be Institutionalized? The Case

of Worker Cooperatives," International Small Business Journal, vol 6, n.

4, pp. 10-19.

Ellerman, David, "Management Planning With Labor as a Fixed Cost: The

Mondragуn Annual Business Plan Manual," based on Plan de Gestion Anual de

la Empresa, tran. by Christopher Logan and Francisco Diaz, Industrial Cooperative

Association, Somerville, MA, and School of Management, Boston College, Chestnut

Hill, MA.

Estrin, Saul, and Derek Jones (1987), "Are There Life Cycles in Employee

Owned Firms? Evidence From France," Working Paper No. 962, Centre for Labour,

Economics, March, 1987

Estrin, Saul, Derek Jones, and Jan Svejnar (1987), "The Productivity Effects

of Worker Participation: Producer Cooperatives in Western Economies," Journal

of Comparative Economics, 11, 40-61.

Geoghegan, Vincent (1987), Utopianism and Marxism, London and New York: Methuen.

Greenberg, Edward (1986), Workplace Democracy: The Political Effects of, Participation,

Ithaca, N.Y., Cornell University Press.

Gui, Benedetto (1984), "Basque Versus Illyrian Labor-Managed Firms: The

Problem of Property Rights," Journal of Comparative Economics, 8, pp. 168-181.

Hacker, Sally (1988), "Gender and Technology at the Mondragуn System of

Producer Cooperatives," Economic and Industrial Democracy, 9, 2, pp. 225-243.

Hirschman, Albert (1977), The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments

for Capitalism Before Its Triumph, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press.

Hoover, Kenneth (1991), The Elements of Social Scientific Thinking, 5th ed.,

New York: St. Martin's Press.

Hoover, Kenneth (1990), review of Making Mondragуn, in The American Political

Science Review 84 (March) 1, pp. 351-52.

Hoover, Kenneth and Raymond Plant (1989), Conservative Capitalism in Britain

and the United States: A Critical Appraisal, London and New York: Routledge.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss (1972), Commitment and Community: Communists and Utopias

in Sociological Perspective, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Kumar, Krishan (1987), Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times, Oxford, Basil

Blackwell.

LeWarne, Charles (1975), Utopias on Puget Sound, Seattle: University of Washington

Press.

Lutz, Mark, and Kenneth Lux (1988), Humanistic Economics: The New Challenge,

New York, The Bootstrap Press.